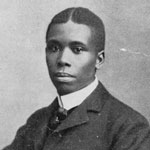

On May 2, 1893, Paul Laurence Dunbar in Chicago wrote a long letter to James Newton Matthews, a country doctor and poet from Mason, Illinois. Paul was 20 years old and in Chicago for the World's Columbian Exposition, where he hoped to find employment and a broader audience for his writings.

I am here in the World's Fair City in quest of work. I make no pretentions to liking this place. There is altogether too much noise, bustle and confusion for me, but I am here to make money if I can. As yet there is no opening for me, but I feel hopeful that there will be soon. I had intended to try doing some World Fair letters to a small syndicate of papers, but every paper to which I broach the subject seems to have made other arrangements. So I shall have to relinquish the idea.

On Monday, opening day at the Fair, Chicago was a revelation to me. People of every color and nationality were to be seen upon the streets. I looked a little while, but I was not used to such scenes and I must confess that my brain was whirling so with a sigh, "Oh cosmopolitan Chicago thou makest me sick." I sought my room and remained there for the rest of the day. I cannot stand crowds. At three o'clock in the afternoon there was said to have been 450,000 tickets sold to the grounds and I mutely thanked my Maker that I had not gone out to be in the crush.

Paul Laurence Dunbar to James Newton Matthews, May 2, 1893. Paul Laurence Dunbar Papers, Ohio History Connection (Microfilm edition, Roll 1).

Paul lived in Dayton when the city had less than 70,000 residents. Chicago had more than one million, and the Columbian Exposition drew visitors from around the world. An immense crowd gathered on opening day.

Never did the sun look down on a grander scene than at noontide yesterday when it shone on the splendid pageant that marked the opening ceremonies of the Columbian Exposition. They crowded platform and plateau, numbering over a quarter of a million of the human family, and such an assemblage as has never before been noted in the annals of the world. They represented every clime and every race, every class and condition of life, every department of thought, and every division of achievement. They made up the grandest and noblest gathering ever known to civilization. On the plateau was massed a mighty multitude, a vast assemblage of the free citizens of the greatest among commonwealths. Surging like a veritable sea of humanity, the immense concourse crowded the spacious square until every foot of ground was occupied, when it overflowed through the adjacent thoroughfares and across the bridges, where the dimensions of the great gathering could be traced no further. The balconies, porticos and roofs of the surrounding buildings were also surrounded with spectators. Thousands of the more adventurous climbed to giddy heights and, on turret, parapet and dometop, looked like pygmies no bigger than a man's hand.

"How it Was Opened." The Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois). May 2, 1893. Page 1.

A few days later, Paul wrote to his mother Matilda in Dayton, telling her about his activities at the World's Fair. Before coming to Chicago, Paul worked eleven hours a day and earned $4 a week.

It is now half past eleven but it is with pleasure I sit down to answer your welcome letter which I received on getting home this evening. You will be glad, I am sure, to know that I have gone to work out at the World's Fair Grounds, at $10.50 a week. My job is a soft snap, I help attend to a gentleman's toilet room, go on at 2:00 in the afternoon, come off at 7:00. Five hours a day at $1.50 a day is pretty fair, I think. If I can get anything better I will take it but I'll hold this one until I do.

My trunk is here all right and I am working in my old black clothes, although they do look shabby out here, for all the young colored men go dressed up all the time. I am somewhat better satisfied than I was at first but my timidity and shyness among strangers holds me back out here. I am too much like a green country boy, in spite of my "extensive travels."

Paul Laurence Dunbar to Matilda Dunbar, May 4, 1893. Paul Laurence Dunbar Papers, Ohio History Connection (Microfilm edition, Roll 1).

Paul's employee identification card for the World's Columbian Exposition is on display at the Dunbar House.

In a newspaper essay about the World's Fair, Paul expressed his displeasure about the high price of food on the grounds.

There are plenty of places where if you are a common person you can get a good common meal for twenty-five cents, or if you are above common feeding, you can get a meal according to your pocket from fifty cents up to fifty dollars. There is no place on the grounds that can be said to be really "cheap." But there are many restaurants where you can eat your fill at a reasonable price. There will be places where they will ask you twenty cents for a sandwich, ten cents for a cup of coffee, five cents more if you put cream in it and ten cents for a small glass of beer; you will be perfectly justified in asking the prices in such a place and then leaving it immediately. It is extortion and neither the Chicago press nor people approve it.

Unidentified newspaper essay by Paul Laurence Dunbar. Published in In His Own Voice, edited by Herbert Woodward Martin and Ronald Primeau. Ohio University Press (Athens, Ohio). 2002. Pages 211 - 212.