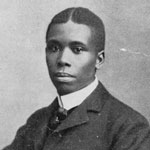

On February 13, 1899, Paul Laurence Dunbar made a public appearance at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City. The event was a fundraiser for the Hampton Institute, a Virginia school that provided vocational training to African Americans.

The birthday of Abraham Lincoln will be celebrated in a variety of ways today by the people of this city. The day falling this year on a Sunday, the anniversary will be commemorated on the day following. The events of the day will interest all classes and races, and promises to be as democratic in its observance as the man whom the celebration honors could have wished.

Benefit for Hampton Institute: Negro songs and stories, under the direction of the Armstrong Association. Waldorf-Astoria. 2:30 P. M. Paul Laurence Dunbar to read from his own works.

"Lincoln Day Celebration." The New York Times (New York, New York). February 13, 1899. Page 18.

An entertainment is to be given on the afternoon of Lincoln's Birthday, February 13, under the direction of the Armstrong Association. The Association is organized to stimulate public interest in the work of the Hampton and Tuskegee Institutes in the industrial training of the Negroes of the South. The program of the proposed entertainment is "Negro Songs and Stories," sung and told by representatives of the race. Paul Laurence Dunbar, who delighted a similar audience in New York a year ago, will read from his own works.

"Lincoln Day Entertainment." The Mail and Express (New York, New York). February 7, 1899.

The weather in New York that day was very cold and snowy, and as a result the program did not start on time.

With the advent of the snowstorm early Saturday evening, the mercury began gradually to crawl up the tube. The cold was still extraordinary, however, and the hand of winter did not relax its grasp. In all about five inches of snow fell.

"Continued Cold and Snow." New-York Tribune (New York, New York). February 13, 1899. Page 1.

While waiting for the event to begin, Paul gave an impromptu interview with a newspaper reporter, expressing his opinions about African American literature. He said the work of Black writers need not be fundamentally different than that of whites, and resisted the idea that he should be limited to writing dialect poems about plantation life.

The entertainment given yesterday at the Waldorf-Astoria for the benefit of the Hampton Institute was slow in beginning, audience and principals being alike held back by the storm. One by one came in the cheerful black faces of Hampton students, members of the quartet, who were down to sing spirituals and folksongs; then Henry T. Burleigh, the soloist, Paul Laurence Dunbar, who was to give an author's reading, and Charles W. Wood of Tuskegee, who was to read selected pieces.

As this interesting group of men of the Negro race, standing by one of the windows where all outside showed white with flying snow, fell to talking the reporter joined it, turning to Mr. Dunbar with this question:

"In the poetry written by Negroes, which is the quality that will most appear, something native and African and in every way different from the verse of Anglo-Saxons, or something that is not unlike what is written by white people?"

"My dear sir," replied the poet, "the predominating power of the African race is lyric. In that I should expect the writers of my people to excel. But, broadly speaking, their poetry will not be exotic or differ much from that of the whites."

"But surely, the tremendous facts of race and origin -- "

"You forget that for two hundred and fifty years the environment of the Negro has been American, in every respect the same as that of all other Americans. We must write like the white men. I do not mean imitate them; but our life is now the same." Then the speaker added: "I hope you are not one of those who would hold the Negro down to a certain kind of poetry -- dialect and concerning only scenes on plantations in the South?" This appeared to be a sore point, and the questioner at once truthfully denied having any such desire.

"Negro in Literature." The Commercial Advertiser (New York, New York). February 14, 1899.